Today, the 1st of February, marks the 55th anniversary of the first-ever international Trade Fair event held in Accra, from 1st to 19th February, 1967. The Fair could have been dubbed the “Second Scramble for Africa”, except that this time, the target was not a slice of Africa but a chunk of a 80-acre site in Accra, the capital city of Ghana. Aimed at creating an atmosphere of confidence and trust for foreign investment in the country, the Fair was themed, “Developing Africa”.

The time for the Fair’s closing event was strategic, coinciding with the first anniversary of the overthrow of Nkrumah, on 24th February, 1966. The event was to be a state-sponsored grand banquet, to be held on the same 24th, was to be attended by diplomats and government officials, industrialists and businessmen, trade missions and delegations, and such VIP and guest participants. The message to the world was that an ‘Nkrumahless’ Ghana can, and does have a promising and progressive future. To any other Ghanaian, however, the Trade Fair was a two-week international funfair, with thirty-one countries across five continents and with about two thousand international manufacturers in attendance. However, this time in history was the height of the Cold War and ‘fun’ could not be used to describe the sentiments of some participating nations at the Fair.

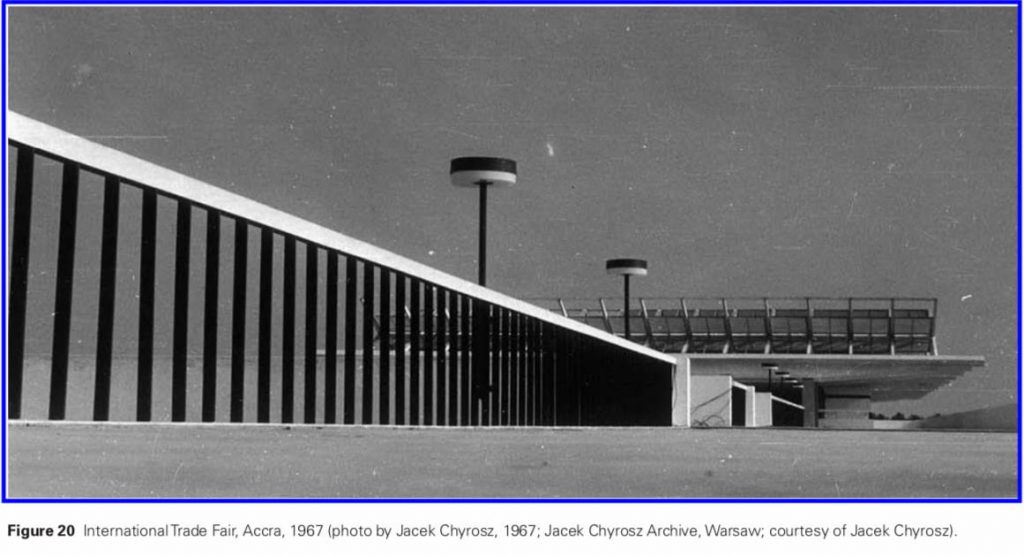

The construction of the International Trade Fair site was one of the grandest projects that Nkrumah started in 1962. His vision was to make Ghana visible to the rest of the world, showcasing the country’s vast mineral wealth and resources, bright investment opportunities, and concerted efforts to become an industrial superpower in Africa, a dream achievable by inviting international cooperation and investment. For this purpose, the government acquired a full 127-acre site at La, south of Accra. And the project was to be complemented with leisure, culture, and sports facilities. Under the direction of Ghanaian Chief Architect Victor Adegbitey and Polish Architect/ Designers Jacek Chyrosz and Stanislaw Rymaszewski, the project was constructed by the Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC). For the Polish socialist architects, coming to work in Ghana, the first country to become independent in Africa south of the Sahara, must have been a privilege enough. Even more so, it was more than just an opportunity of being part of building modern Accra, it was also being part of erasing a Western colonial legacy.

To give concrete expression to Ghana’s vision for international trade, the three put in their best to design a remarkable architectural edifice, an edifice destined to become one of the most magnificent modernist structures on the African continent at the time-the Africa Pavilion. The most unique feature of this visually striking piece of architecture was its imposing 62-meter diameter disc canopy, which was suspended above a circular body elevated on columns and surrounded by vertical fins. Another of its outstanding features was a 198-meter ramp leading 12 meters up, allowing vehicles to drive up the building. According to Rymaszewski, this futuristic design concept was inspired by the royal umbrella of Akan chieftains. For decades, architectural history scholars regarded this impressive architectural masterpiece as an icon of modernist architecture, and as a symbol of Africa under an umbrella of unity.

Construction of the project came to a brief halt with the news of the overthrow of Nkrumah, on the fateful morning of 24th February 1966. Unlike many grand industrial projects which did not receive notice to continue, the Trade Fair project was given less than a year to complete.

By January 1967, the dailies had started advertising the upcoming international event, charging the atmosphere with high expectations of a new age of prosperity for Ghana. The foreign exhibitors had started arriving by sea, air, and land. They fast filled the luxurious Ambassador, Continental, and Star hotels to capacity, setting up their stands at the fair by day, and enjoying Accra nightlife long after daytime. Traffic jams suddenly surged in Accra, with the influx of visitors from the countryside and beyond.

On 1st February, that bright and bright sunny morning, all roads led to the Trade Fair grounds. The fair was opened by Lt. General J. A. Ankrah, leader of the National Liberation Council at the grand African Pavillion. He was accompanied by the top brass of the Ghana Armed Forces and the Police Service. Together with their large entourages, traditional paramount chiefs, kings, and queen mothers also attended the event: the king of the Ga State of Accra, Ga Mantse Nii Amugi II; the king of the Ashanti, Asantehene Otumfuo Sir Osei Agyeman Prempeh II; Okyehene of the Akim Abuakwa traditional area, Nana Ofori Atta; the Tumu Koro, president of the Northern Regional House of Chiefs. They all arrived in their unique pomp and pageantry, accompanied by traditional drumming and dancing. They graced the occasion with such a display of rich Ghanaian culture as has never been seen before in one place. They held distinguished guests from various countries spellbound. Air Vice Marshall Otu gave the opening address after General Ankrah cut the ribbon declaring the Fair open. The music by the army brass band was drowned, as the cheering crowds were treated to a breathtaking jet fighter and helicopter aerial display by the Ghana Air Force, making the atmosphere explode with excitement. On each of the following days, crowds of about 20,000 would form unending serpentine queues hundreds of meters starting from the gates.

Inside the Fair grounds, it was an exciting atmosphere full of people of various nationalities, a place dotted all over with pavilions and stands of exhibitors, a place ‘jamming’ with loud music and with more than enough food and drink stands to feed the crowds. One of the most patronized stands by both locals and internationals was the Club Beer Garden – the Accra Brewery pavilion, of course – serving its chilled premier lager, the soul of Ghanaian leisure. The Ghana Bottling Company stand served Pepsi-Cola and Mirinda. The Ghana Cocoa Products Corporation gave free cocoa drinks to all. Go-Carts, provided by the Tema Chocolate Factory, whizzed to and fro, transporting hundreds of passengers to the far ends of the Fair. There were over 200 stands at the Fair – food plazas and a large playground for children. The drinking bars featuring popular live bands such as Brigade Mysterious Combo Band, as well as the open-air theatre performances by the African Theatre Group, giving the Fair a theme-park spark in the evenings.

The host country, Ghana, put on its best display in agricultural production. The Agricultural Development Corporation and the Cocoa Marketing Board displayed good quality cocoa, as well as commercial crops such as soya bean, castor plant, coffee, and palm kernel. On exhibition was a range of agricultural machinery at the United Ghana Farmers’ stand. At the pavilion where the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) was represented, it was all about ‘Made in Ghana’ products from its subsidiaries: Ghana Cigar Company, Ghana Match Company, Pioneer Biscuit Company, Ghana Laundries, and Ghana Furniture and Joinery Limited. In the Mala Pavilion, the Ghana National Trade Company (GNTC) put on the “Ideal Home Show”, to showcase the new living standards for the modern African family. In the Productivity stand, The Ghana Manufacturing Company Limited was crowded with visitors in awe of new designs of bags of all kinds – handbags, briefcases, and school satchels. The main aim was to compete with the ubiquitous ‘Made in Japan’ and ‘Made in Hong Kong’ labels in Ghanaian homes. Also attracting much attention was the new fufu-making machine by Ghanaian inventor Mr. S.K. Cherbu. Timber Ghana, by the Takoradi Veneer and Lumber Company, was an impressive pavilion, an exhibition of the country’s abundant timber species, eager to attract foreign investors into the production of veneer plywood, furniture, flooring, doors, cabinetwork, mouldings and joinery. The Consolidated Africa Selection Trust (CAST) stand exhibited its impressive array of diamonds, while the Volta River Project stand exhibited the success of the Volta Lake, Ghana’s greatest achievement – the largest man-made lake in the world. Ghana’s premier technical university, the then University of Science and Technology, was represented by its School of Architecture at its stand in the form of a Geodesic Dome.

In the Africa Pavilion, a host of African countries were present to support Ghana’s efforts, in the spirit of comradeship and African unity. At 4 o’clock every afternoon, shoulder-rubbing crowds gathered to watch spontaneous concerts of cultural dances and displays from these African countries. The best of Nigerian, Ivorian, Togolese, Liberian, Nigeran, and Moroccan culture was on lavish display, with music, fashion, traditional arts, and a wide range of products – cloth and fabric and textile print, metalwork, and woodwork, household items made from cane and bamboo, jewelry and pottery, and handcrafts including terra cotta art objects.

The most active country at the Fair was probably India, Ghana’s long-time partner in the Non-Aligned Movement. At India’s pavilion, the Great Maharajah Restaurant was open at all times to passersby curious and adventurous enough to try the exotic Indian cuisine. Chellarams, one of the oldest Indian retail merchant companies in Ghana, was present, with multiple stands. On display at the Indian pavilion were products from various provinces of India. There were woven rugs, silk cloth, brassware, embroidery, colored silk, silver, and ornamental jewelry. 8th February was India day. The Indian pavilion attracted a lot more crowd with entertainment, with nothing short of a live Bollywood experience. The talk of the fair was the bevy of exquisitely beautiful young Indian women who served as attendants at the Indian stand. There were also the Indian models for the fashion parades and the dancers at the cultural show from Bengal. The shows ended with an open-air cinema showing Indian films, and finally with a display of sensational fireworks.

To the excited and elated Ghanaians, the electric atmosphere at the Miss Trade Fair 1967 contest and the Kumasi Brewery Hi-life Dancing Competition Championships, it would not be easy to perceive the hostility between two elephants in the room: the palpable tension between the exhibitors from the Western capitalist countries and the Eastern communist-socialist countries, towards whom Nkrumah was quickly building Ghana’s ideological leanings and development preferences. This was most obvious at the China pavilion, which was not really of China, but of Taiwan. The Soviet Union was nowhere to be found. At the China pavilion was an impressive huge ‘Great Wall’ of a China-themed castle, but its supervisors were in a somber nervous mood because China had broken off all ties with Ghana since Nkrumah’s overthrow. In mass repatriation, just a few months before, 430 Chinese security advisers, technicians in fishing and construction, as well as embassy staff, were deported from Ghana, along with hundreds of Soviet advisers. To the Chinese, without their political comrade in power, a display of textiles and textile production machinery and technology was a futile endeavor. These were uneasy times for communism, with Ghana under the CIA puppet military junta that had taken over the country. At the architecturally pleasant Israel stand, the Israelis, with whom Kwame Nkrumah had a tricky Kweku Ananse friendship, were perhaps wise to have put up a rather modest display of kitchen and other home items, construction equipment, and sanitary ware, all of which was not reflective of their large investment portfolio of business in partnerships with the Ghanaian government at the time.

What chances did the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) stand against their West German counterparts at the fair? In front of the West Germany pavilion was a fascinating dancing fountain that rose 6 meters into the sky and fell in synchrony with European classical music. As if that was not impressive enough, inside the pavilion were stands representing multinational industry giants – like Siemens, Bosch, Thyssen, Stinnes, Wolff, and Klöckner. There also were C. Woermann, agent for German Equipment Brands, and Technical Lloyd Limited, agent for BMW luxury cars and motorcycles, which were well-established automobile brands in Ghana. The automobile industry in West Germany had grown powerful globally. Having joined forces with the likes of Ford, brands such as VW, Audi, Daimler, and Benz, spread to the USA, with American subsidiaries. The East German brands, such as the box-shaped Trabant and Lada, had been growing in numbers on Ghanaian streets in recent years, but now, the preference of Accra residents swayed towards the sleek BMW, Benz, Ford, and Opel. At the stand for RT Brisco Ghana Limited, distributors of Benz buses and luxury cars, patronage steadily rose, as the days went by since prices were now agreeable with the pockets of the averagely wealthy Ghanaian.

The America Pavilion, arguably the largest of them all, was an umbrella for companies from the USA, some already operational in Ghana. These included Singer, the sewing machine company from Boston; the Pioneer Tobacco stand, (PTC) a subsidiary of the British American Tobacco Producers of Cigarettes; the NCR stand, which sold mainframe computer systems; Firestone Tyres; and USA Motors, distributors of Pontiac sedans and station wagons like Buick, Chrysler, and Cadillac. The Western capitalist giants were, once again, reinforcing their grounds on African soil against the communists.

As time went on, The Hungary and Poland stands became less vibrant. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) stand put up a fight, organizing a fashion show which failed to draw the crowds. The sturdy Pentacon Pentina and Praktica camera, as well as other less well-known electronic brands, won the hearts of Ghanaians, even though this was not without a struggle for attention from brands like Philips, which was exhibited at the French Societe Commerciale de l’Ouest Afrique (SCOA) stand. SCOA sold everything Philips: radios, table fans, record players, lamps, radiograms, ceiling fans, tape recorders, sound amplifiers, fluorescent lights, and other household appliances. These would slowly wipe off brands from the socialist countries on the Ghanaian market. One of the brands to survive was Bata footwear, and this was due to its grounded popularity on the Ghanaian market. And so at the Czechoslovakia pavilion, Bata footwear was well patronized.

One must agree that seven years of socialist-oriented policies in Ghana was not enough time to cause a dent in the amour of two particular giants that were stationed at the UK pavilion, one of the most prominent pavilions at the Fair. One giant was the British United Africa Company (UAC), now known as Unilever. The other was the Anglo-Swiss company, Nestle Products (Ghana Limited), producers of Milo, Ideal Milk, Cerelac, and Lactogen, the infant milk formula. These two had the African tongue enslaved. They had powerful control over the consumer behavior of Africans. Nkrumah did call the Kingsway “a necessary evil”, in 1956, at the opening of the new Kingsway department store in Accra. The UAC had acquired many brands of home consumables, the products of which it supplied to Africans. Among these products were soaps and shampoos, body lotions and creams, deodorants and hair products, and even frozen foods. Popular brands at the time were Comfort, Dove, Lifebuoy, Omo, Rexona, and Sunsilk. Also present with retail products from all over the world was the United Trading Company (UTC) stand of Basel Switzerland, the largest trading house with roots in Ghana since colonial times.

When the ‘big boys’ Mr. D. E. C. Steel, the British Petroleum (BP) Managing Director for West Africa, and Mr. George Thomas, the British Minister of State for Commonwealth Affairs, arrived to open the UK pavilion, the communists read the writing on the wall: that the West was not ready to lose trade turf in Africa to the East. In an open speech, Minister George Thomas assured Ghana of the UK’s support for the military government. He also promised to send the British National Export Council and the Federation of the Commonwealth Chamber of Commerce to assess Ghana’s wealth. Thus, the message was clear: for the superpowers, which include the British,French, and Americans, the International Trade Fair was a platform to display commercial superiority, a silent cold war that would be waged throughout Africa, starting from Nkrumahland. And woe unto any leader or anyone who stood in their way.

For Ghana, the maiden Trade Fair of 1967 was the first climax of the roller coaster ride, one from which Ghana later descended into the economic dark ages of the 1970s. It was the first battle that silently indicated the fall of communism and socialism in Africa. With Nkrumah gone, the old piper was back with the same tune, only with a different flute. Following the laudable compliments on the modernist architecture of the Accra Trade Fair in the international press, Nkrumah’s architectural maverick trio – Chief Architect Victor Adegbitey, Jacek Chyrosz, and Stanislaw Rymaszewski – were asked to stay on to “help develop Ghana”. However, they would subsequently receive thin slices of the architectural commission cakes, while the fatter slices went to British firms that had established themselves in the country since the pre-independence era. By the mid-1970s, the trio had left the country for good.

Many more Trade Fairs were held in the following decades, but with declining vivre. By the early 21st century, the place had fallen into disrepair, and the African Pavilion, now a ghost of its former self, in 2007 lost its iconic crown to the crosswinds and neglect, an sad epitaph to modernist architecture in West Africa.

In 2019, the government of Ghana had the Trade Fair demolished, except for what remained of the Africa Pavilion. The Trade Fair has been redesigned by the renowned British Ghanaian Architect, David Adjaye, under the auspices of the Ghana Export Promotion Council. It has been divided into lots in hope of attracting long-term lease and investment. Today, it is a wasteland of bushes and rubble upon rubble, of snakes and scorpions and the wild.

Will the Accra Trade Fair be added to the list of proposed projects that never see the light of day? Will the canopy of the African Pavilion be restored to its former glories or will it be left to crumble into another faded memory? While we are at these, it also must be asked how important architecture and spatial memory are to the development of Ghana. And even as we envision new spaces of the future, and in some ways redefine or disregard the old, may we never forget that these same spaces hold more significant histories of a bygone era from which we may derive great value to enhance newer visions.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Professor Lucaz Stanek, author of Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa and the Middle East in the Cold War (Princeton UP, 2020), around whose research this narrative is built. I thank archival assistants Millicent Aryee and Nana Yaa Okyere at Public Records and Archival Administration Department (PRAAD) for gathering the information from the 1st to 19th February 1967 editions of the Daily Graphic, which are the main source for this piece. Also, I thank Makafui Sitsofe for his digital model of the Africa Pavilion.